A little something to go with breakfast …

It seems that whenever humans create technology to solve a problem, we end up causing detrimental side effects. We created the internal combustion engine, which is less than 30 percent energy efficient, and gave rise to asbestos, chromium, lead, and methyl tertiary butyl ether (MTBE) contamination of air, lakes, and aquifers, and escalating asthma rates in our children— to name just a few consequences. We created wood-pulp based paper and are subsequently responsible for clear- felled forests, erosion, spoiled rivers, collapsing ecosystems, and mercury poisoning. Plastics pollute with dioxins and mostly aren’t biodegradable; thousands of new chemicals have never been tested for toxicity; and there’s that most dangerous of substances— nuclear waste. On the other hand, when nature seeks to solve a problem, it resolves all associated problems. Take, for instance, the humble egg. It’s streamlined, so it can be laid with the minimum of discomfort to Mom. In fact, it’s so streamlined that it’s the shape a rectangular brick will be turned into by nature, if left long enough in a flowing stream. We all know how thin an eggshell is. The hen uses the least amount of energy and materials in its creation so as not to deplete her own calcium levels. If she can’t replace the calcium needed to make eggshell quickly enough through her diet, she extracts it from her skeleton, causing a condition known as avian osteoporosis, and even her own demise. While fragile enough to break from the inside when pecked at by a delicate, hatching, chick, the shell is incredibly strong under compression from the outside. In 2001, scientists duct- taped a raw hen’s egg to the side of a deep- sea submarine. It descended one thousand meters below the surface of the ocean— a depth that would crush almost anything. The egg returned to the surface intact.

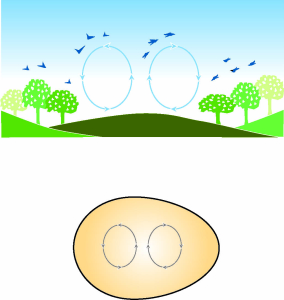

Eggs are also highly thermally efficient. When Mrs. Hen needs to take a walk for food or other necessities, the egg holds and recirculates its heat efficiently so that it doesn’t cool down too much during her absence. The egg is also optimized for nutrient distribution. Both its heat and nutrients flow in a highly efficient, doughnut- shaped ring vortex, perfectly matching the shape of the egg. Many eggs are elongated at one end. This out- of- round shape means that should an egg roll out of its nest, it will tend to roll back toward it again—handy if you’ve laid your offering on a cliff ledge. If the egg does take a fall, it has a shock- absorbing air pocket at the larger end. This also doubles as a pressure- relief valve if the egg gets overheated, since the air pocket compresses and protects the shell from expansion forces. The shell also offers the dual features of keeping out dirt and water, while being microscopically porous so that the developing chick gets oxygen as needed. Clearly, a number of adaptive strategies are related to an egg’s shape— which matches the proportions of nature’s spiraling whirlpools. These proportions can result in an infinite number of variations; hence we see many varieties of egg shape and size that all share similar benefits. Beyond all these attributes, the egg is entirely recyclable and leaves no deleterious residue.

Excerpt from The Shark’s Paintbrush, copyright Jay Harman. All rights reserved.